Pulling together the threads of Ricoeur’s theory of narrative: prefiguration, configuration, refiguration.

In the last few posts I have introduced Paul Ricoeur’s philosophy of narrative, placing it over against theories of narrative derived from structuralism. He uses the term ‘mimesis’ extensively in his examination of narrative, a technical term in linguistics and philosophy that essentially means the imitative representation of the real world in art and literature. Ricoeur’s use of ‘mimesis’ and ‘mimetic’ is idiosyncratic and I’ll talk about it in more detail in the near future, as I’ve already promised.

I’ve also set out the details of Ricoeur’s narratology, describing the three moments of narrative:

- I first looked at prefiguration (mimesis 1) and narrative competence, and the pre-existing experience and expectations of stories we bring with us when reading.

- Next, I described configuration (mimesis 2) and narrative emplotment, about characters, events and the point of a story as a whole, about following the rules and transgressing them too.

- And thirdly, I talked about refiguration (mimesis 3), understanding and transformation, as readers complete a writer’s story in restoring it to the real world of action and suffering.

A brief summary is helpful at this point.

The distinctive characteristic of Ricoeur’s philosophy of narrative is that it approaches the subject with a significantly wider view than the structuralist models that had previously dominated.1

Structuralist narratology is solely concerned with the closed system of the story being narrated and as such it is directed almost exclusively at mimesis 2, the configuration of the narrative, and even then it is a sub-set of Ricoeur’s full proposition for mimesis 2. The fixation on deep-level structure in the structuralist models — that all stories ever told conform to set of patterns and rules, have a defined set of character types and roles, follow a systematic sequence of emotional ‘beats’, and so on — miss out on surface-level facets like characterisation, reversals of fortune, the temporality of events and the like.2 It certainly has no conception of the act of emplotment or the notion of narrative tradition.3

Ricoeur’s wider view incorporates two vital extra domains discussed in those earlier posts.

Firstly, what is believable as a story is contingent on the prefigured worlds of authors and readers.

And secondly, the world of the story is restored to the real world through the refiguration of hearers and readers.

Ricoeur’s recognition and exploration of these two vastly significant arenas indicate the severe limitations of any notion of narrative built on pure structuralism, and it is the crucial role of mediation that configuration plays between prefiguration and refiguration that spotlights the poverty of structuralist narratologies.

A mimetic theory of narrative, then, pays great heed to the world that is being brought to a given story, and to the possibilities for transforming that world.

What we bring …

Hearers and readers are framed in their capacity to follow a story, and so to believe in it, by the matrix of stories they have previously heard. No two matrices are identical, though there may be huge amounts of overlap.

Certainly those raised in Western Europe, for example, will be thoroughly framed by historical stories like major international wars, fascism and religious factionalism and by political stories like democracy and capitalism. As a result they will be able to engage with each other without the need to vocalise a large number of things since so many perceptions and notions can be taken as given. However, significant differences will inevitably be present within a single society.

People being raised under a meta-story of patriarchy and the pater familias (the head of the family in classical antiquity), such as those from conservative religious backgrounds, say, will have very different reactions to a classic story like Cinderella from people influenced by feminist liberation. But even feminist perspectives pre- and post-Barbie, pre- and post-Thatcher, pre- and post-Madonna, for instance, will be significantly different from each other. And that is even before turning to more particularity due to upbringing, education, sex and gender, economic circumstances, ethnicity and so on.

Added to this is the personal narrative preferences or exposure of an individual that will add up to shape what constitutes ‘a good story’ — diets consisting of broadsheet journalism, escapist ‘beach’ novels, classic French cinema or computer game shoot ’em ups will inevitably produce strikingly distinct perceptions of narrative competence.

Or, to speak more of the era of Jesus of Nazareth, my particular field, and to highlight just a few high-level influences, though the narratives of the Maccabean uprisings would have been available as a shared set of stories, Jews persuaded more by Hellenism (i.e. Greek language, philosophy and culture), by Romanism (i.e. Roman imperialism and civil governance), by fundamentalism, by separatism, by asceticism or by ir/reverence for the Temple in Jerusalem would read them very differently.

… and how we’re affected

Mimetic approaches to narrative also take pains to assess the transformative effect of a narrative on the hearer/reader.

Of particular interest is the manner in which the world proposed by the text, the way of being-in-the-world presented by the narrative, reinforces, challenges or contradicts the world of the reader, and the reader’s response to that interplay.

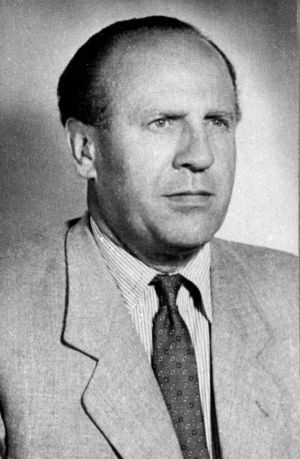

As a brief example, over against a naïve received opinion that all Germans were Nazis between 1933 and 1945, the film Schindler’s List presents a different view that portrays both the horror of the six million people killed in the Holocaust (without ever being able to represent the Holocaust in its entirety) and the surprise of six hundred who were not because of the actions of a German.4

Through this encounter with an alternative reading of a received story, the reader is able to project herself into the story and ask ‘Would I have been like Oskar Schindler? Or like Itzhak Stern, Oskar’s Jewish assistant? Or maybe like Amon Goeth, the camp commander?’

Importantly, Schindler’s List is not a documentary but a fictionalisation inspired by the life of Oskar Schindler, blurring the lines between fiction and history, and as such it clearly illustrates the mimetic nature of art imitating life.

Emplotment, mediating between what we bring and how we’re affected

Emplotment, or configuration, plays a mediating role between prefiguration and refiguration. A story can only work if it is recognisable as a story in reference to the author’s and the reader’s prior understanding of a believable story. But a story can also only work if it says something about something to somebody, if it refers afresh to the real world.

Ricoeur is particularly concerned with narrative’s ability to refigure time, especially events in time, and especially since time is so hard to understand in literal language.⁵

It is to this issue that I shall turn next.

Photo credits

Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Oskar Schindler, via Wikimedia Commons

Footnotes

-

Ricoeur, Time 2, 31–61; Blundell, Paul Ricoeur, 70–72.

-

Blundell, Paul Ricoeur, 78; Stiver, Theology after Ricoeur, 62.

-

Cf. Paul Ricoeur, ‘Interpretive Narrative’ in Paul Ricoeur, Figuring the Sacred: Religion, Narrative and Imagination (ed. Mark I Wallace; trans. David Pellauer; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995), 187–91 [181–99].

-

Schindler’s List (1993). Directed by Steven Spielberg. Los Angeles: Universal Pictures. Based on the book Schindler’s Ark, by Thomas Keneally.

-

Ricoeur, Time 3, 27, 267.