Configuration is the second moment of mimetic narrative, all about emplotment — about characters, events and the point of a story as a whole, about following the rules and transgressing them too.

The second stage of mimesis, mimesis 2, but which Ricoeur rather more floridly calls configuration, corresponds to narrative in its most commonly-understood sense: that act of telling or receiving a story, the actual configuration of a given plot — the story as told, or as read.

The ‘configuration’ stage of mimetic narrative is the stage of writing and reading a story — the story as told, or as heard.

However, Ricoeur’s model of emplotment emphasises the requirement that this sense of narrative is placed between the two other senses, mimesis 1 and mimesis 3: this stage of mimesis follows an early stage and precedes a later one.

Though that sounds obvious, it has significant implications.

Finding itself in between, mimesis 2, configuration — the act of emplotment — plays a mediating role between the other two.1

Mediation is a significant feature of Paul Ricoeur’s approach to philosophy, and he often examines the mediating function of an idea between two opposing positions.

Here, the mediating function of narrative configuration leads Ricoeur to prefer the term emplotment to plot because it implies an active and dynamic quality to mimesis 2 that stresses its mediation between the ‘pre-understanding’ already discussed and the ‘post-understanding’ that I shall address presently.2

Ricoeur offers three ways in which emplotment mediates.

1. Mediating between individual events or actions and the plot as a whole

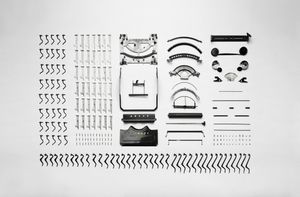

Firstly, it mediates between individual events or actions and the plot as a whole. It makes a meaningful narrative from an assortment of events.3 Or, conversely, emplotment draws together a set of diverse events into a meaningful whole to create a story.4

There is something synecdochic about this interaction. The singular event gets its meaning only in relation to the whole story and the part it plays in developing the plot.

At the same time, the whole story cannot be just a collection of events put in an order but a weaving into an organised and intelligible whole.

‘In short, emplotment is the operation that draws a configuration out of a simple succession.’5

2. Mediating between characters, events and actions to develop the plot

Secondly, emplotment draws together agents, events, actions, goals, results, circumstances, and so on such that they work in synchrony to develop the plot.

Mediating between these diverse elements enables initially simple plot configurations to be subsequently extended and embellished. Emplotment also includes features such as sudden reversals of fortune (known as ‘peripeteia’), recognitions and such like within the complexities of a plot, and consequently narrative is able to move the paradigmatic prefigured world (i.e. the language and narrative elements in isolation, familiar to writers and readers from the previous narrative experience, their ‘narrative competence’, as previously discussed) into the syntagmatic order of a story (i.e. the language and narrative elements working together in this specific narrative).

Emplotment ‘constitutes the transition from mimesis 1 to mimesis 2. It is the work of the configurating [sic] activity.’6

3. Mediating through temporality: judging and selecting

Thirdly, emplotment is able to mediate through its temporal characteristics. Emplotment includes ‘in variable proportions’ two temporal qualities, ‘one chronological and the other not.’7

The chronological dimension incorporates the episodic nature of a story — the fact that it is made of a sequence of events.

The other dimension is the quality of configuration: that is, in configuring a story one is judging and selecting which events to grasp together, and how to arrange them, into the unified temporal whole of the plot. From a sequence comes a configuration through this twin action of selection.8

The result of this multiplicity of mediation is that the act of emplotment ‘reveals itself to the listener or the reader in the story’s capacity to be followed.’9

To follow a story is to move forward in the midst of contingencies and peripeteia under the guidance of an expectation that finds its fulfilment in the ‘conclusion’ of the story. This conclusion is not logically implied by some previous premises. It gives the story an ‘end point,’ which, in turn, furnishes the point of view from which the story can be perceived as forming a whole. To understand the story is to understand how and why the successive episodes led to this conclusion, which, far from being foreseeable, must finally be acceptable, as congruent with the episodes brought together by the story.10

But is it believable … ?

The degree to which a story’s progression to its conclusion is ‘acceptable’ is of course an expression of how ‘believable’ a listener or reader finds a story. The writer’s plot in a given story sits amongst all the plotted stories the reader has previously read.

Ricoeur’s notion of the mediating interaction of mimesis 2, configuration, with mimesis 1, prefiguration, expresses that a reader’s prefiguration (both in terms of narrative competence and the narratives that have been prefigurative for the reader) is every bit as significant in the reader’s capacity to follow the story as the story’s own configuration.

Further, the fact that the story can be followed allows the dichotomy of (individual) event and (unified) story to be resolved by converting the paradox into a poetic ‘living dialectic.’11

A story’s capacity to be followed means that an entire plot can be brought together under one ‘thought,’ the narrative’s ‘theme.’ It also means that in following a story the end is always in mind, and, especially with a well-known story, the way in which the events lead towards the ending gives a fresh quality to time.

So much for the interaction of mimesis 1, prefiguration, into mimesis 2, configuration. What about the relation of mimesis 2 to mimesis 3, refiguration? Here, Ricoeur offers two features: schematism and tradition.

Schematism, and the productive imagination

The first feature, schematism, illustrates the close relation of metaphor and narrative in hermeneutics, in particular because the act of grasping together diverse events into a meaningful and intelligible whole engages the productive imagination in a profoundly synthetic manner.

The productive imagination ‘connects understanding and intuition by engendering syntheses that are intellectual and intuitive at the same time.’12

In a similar way, emplotment ‘engenders a mixed intelligibility between what has been called the point, theme or thought of a story, and the intuitive presentation of circumstances, characters, episodes, and changes of fortune that make up the denouement.’13

This function of emplotment relies on a framework of rules within which the intelligibility resides, and as a consequence ‘we may speak of a schematism of the narrative function.’14

As with all schema, this one ‘lends itself to a typology,’ most frequently encountered under the rubric of genre.

Footnotes

-

Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol 1., (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 65.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 65.

-

S H Clark, Paul Ricoeur (London: Routledge, 1990), 170.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 65.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66."

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 66–67.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 67.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 68.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 68.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 68.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 68.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 69.

-

Clark, Paul Ricoeur, 171.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 69.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 69.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 70.

-

Ricoeur, Time 1, 70.